🧮 Section 3: Board Setup + Getters

📝 Summary

In this section, you will add the Board class below Cell in model.py. The board owns every Cell and provides safe, read-only access for the Tkinter UI to query the game state.

✅ Checklist

- Add the

Boardclass below theCellclass inmodel.py. - Validate that the mine count fits the board size.

- Build a 2D grid of

Cellobjects. - Initialize internal counters and state flags.

- Add public getters and helper methods for safe access.

🎓 Core Concepts

The board is the “model” for the game. It stores all cells and the rules the UI depends on. By keeping this logic in model.py, the Tkinter layer can remain focused on drawing and user input.

Creating a 2D grid of objects means you have a list of rows, and each row is a list of Cell objects. This layout matches how the UI will place buttons, so each cell’s (row, col) aligns with its position on screen.

Validation protects your program from invalid configurations. If the number of mines is equal to or greater than the number of cells, the game can’t work, so we stop early with a ValueError.

This class also introduces a clean “public API” for the UI:

- Methods like in_bounds(...) and cell(...) are safe ways to access the grid.

- @property methods provide read-only access to values the UI needs to display (flags used, remaining mines estimate, win/loss state).

This matters because the UI should ask the model for information instead of reaching into model internals. If we later change how the board stores its data, the UI can keep working as long as the public methods stay the same.

Finally, notice the underscore names like _flags and _game_over. In Python, a leading underscore is a convention meaning “internal/private.” It’s still accessible, but other code should treat it as “hands off” unless there’s a good reason (like a controlled test).

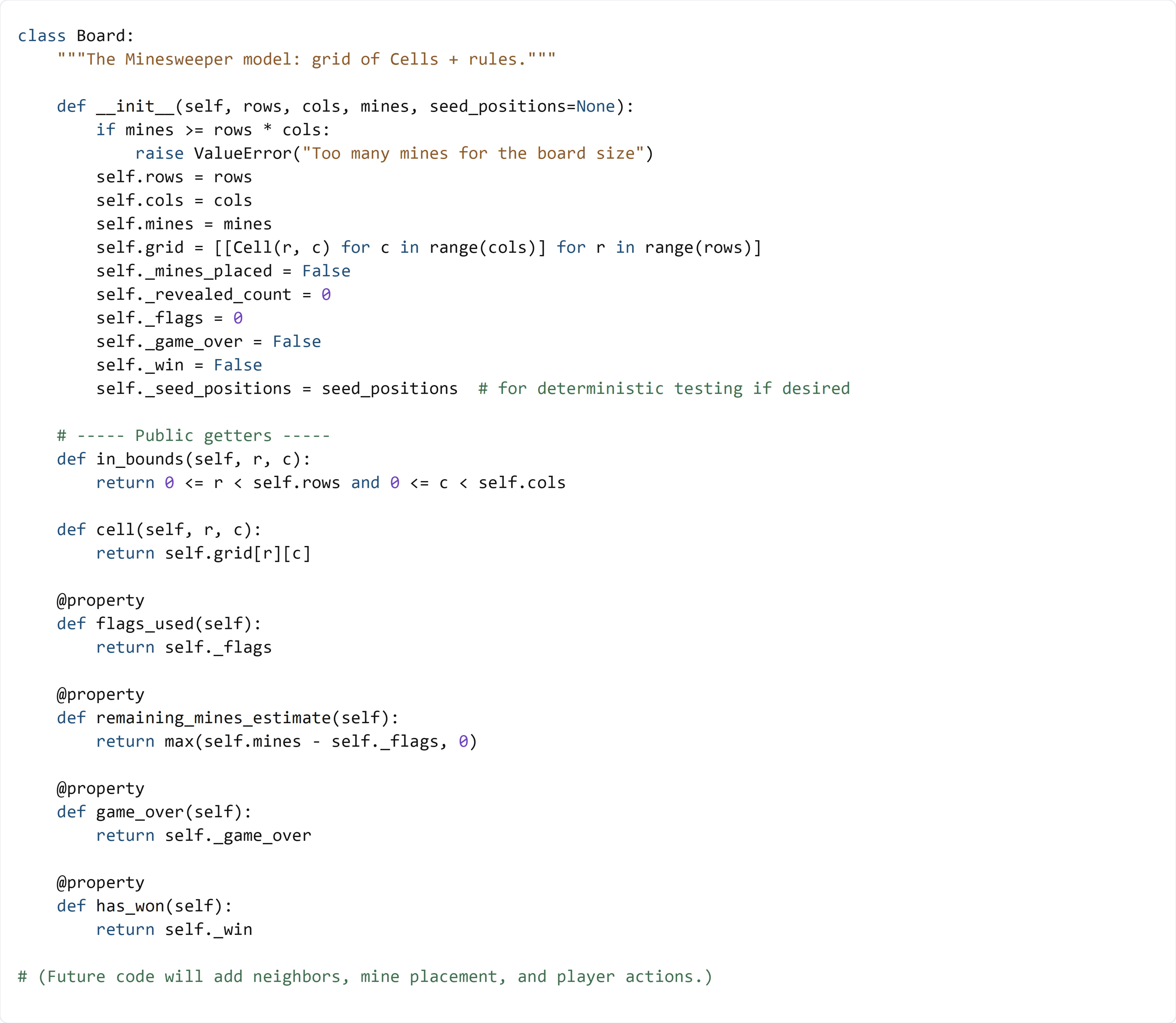

💻 Code to Write (in model.py)

Type this by hand so you understand each piece.

🧠 Code Review & Key Concepts

self.grid = [[Cell(r, c) for c in range(cols)] for r in range(rows)] builds the 2D board where each Cell knows its own coordinates.

if mines >= rows * cols: raise ValueError(...) is an example of defensive programming. It’s better to fail early with a clear error than to build a broken board that crashes later.

The “internal state” variables track what’s happening during play:

- _mines_placed starts as False so we can delay mine placement until the first click.

- _revealed_count helps check the win condition later (all safe cells revealed).

- _flags tracks how many flags the player has placed.

- _game_over and _win store the end-game state.

seed_positions is there for testing and debugging. If you pass a list of mine positions, you can make the board deterministic and write reliable tests.

in_bounds(r, c) is a small but important helper. Anything that walks neighbors (or checks clicks) should use it to avoid out-of-range indexes.

cell(r, c) is an accessor method. It may look small, but it’s a design choice: the UI code should say “give me the cell at (r, c)” rather than touching grid directly.

The @property methods (flags_used, remaining_mines_estimate, game_over, has_won) let the UI read state without directly changing internal counters. remaining_mines_estimate clamps at 0 so the label never shows a negative number even if the player places extra flags.

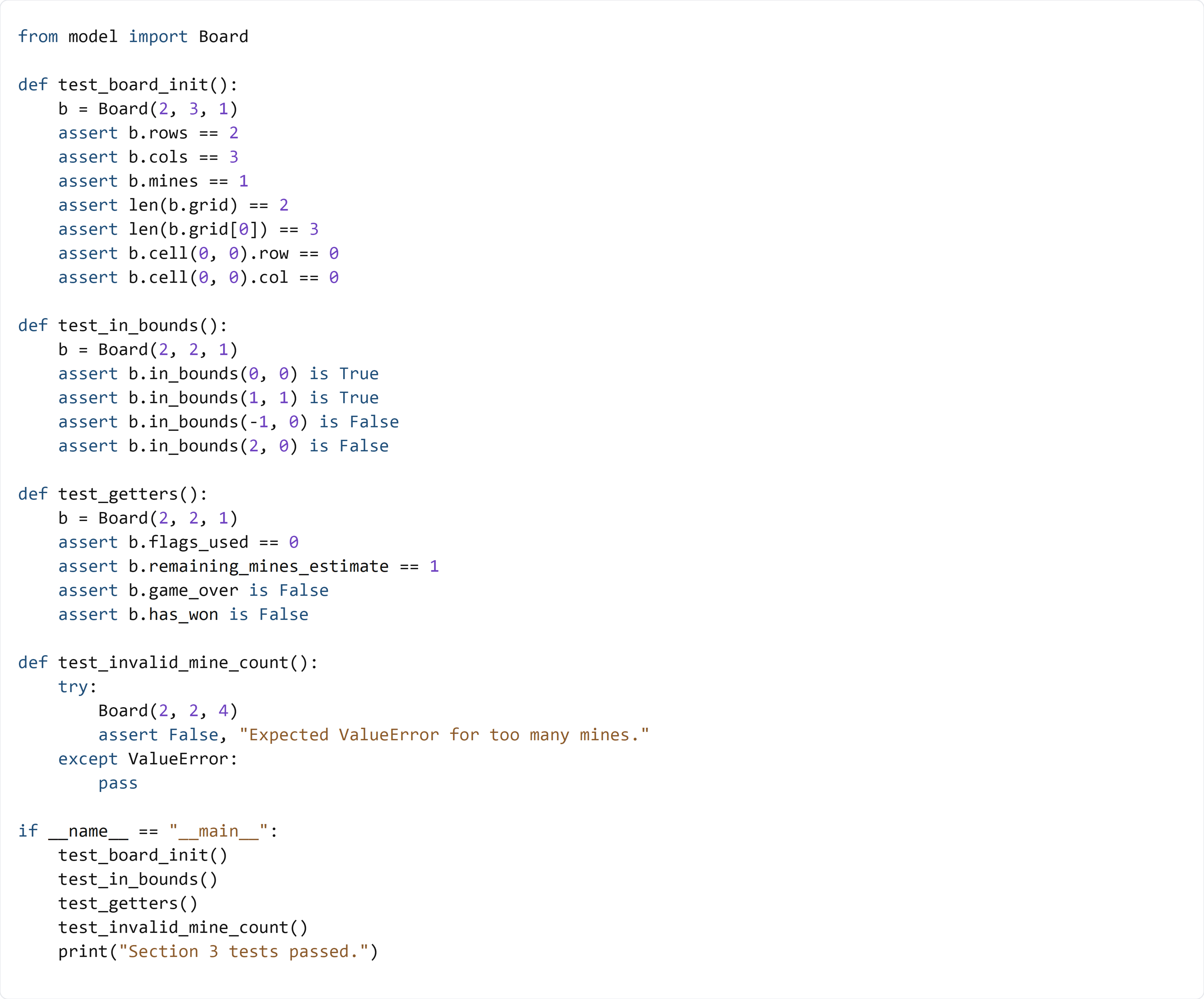

🧪 Test File (create s3_test.py)

This test builds small boards, checks grid sizing, confirms in_bounds behavior, and verifies the read-only getters. It also confirms that invalid mine counts raise a ValueError.